Jump to recipe for pear cardamom strudel

During the spring break of my semester abroad in Ireland, I traveled to Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic with two American friends. We were on tight student budgets, so we didn’t eat many fancy meals out. Instead, we bought cheese, bread and yogurt from grocery stores and picnicked by fountains in public squares. In the evenings, we waited our turn to boil noodles in hostel kitchens.

One day in Germany, we stopped in a bookstore where I found a beautiful Bavarian cookbook. It had hand-drawn illustrations alongside boldly outdated recipes – like stuffed roast pigeon. I fell in love with it, instantly. I agonized over whether to pay the steep price of (I think) 13 euro. After all, that kind of money could buy five to seven hostel spaghetti dinners. With cheese. Eventually though, I decided it was worth it. And a tradition was born. Ever since then, I have collected a cookbook from every country I have been lucky enough to visit.

I do it both because cookbooks are more useful souvenirs than snow globes, and because they show me a way out into the world. See, I know that you can’t really get to know a place without talking to the people who live there. But I’m a textbook introvert who gets anxious during the 120 seconds of “share the peace” at church. And that’s in my home country, with a script. Every time I open my mouth when I’m abroad, I’m afraid I’ll commit some alienating faux pas. Maybe I’ll let the word “fanny” slip while I’m in polite British society, and everyone will freeze and gasp audibly – like the scene in Downton Abbey where Sibyl came to dinner wearing pants.

Ultimately though, I know that human connections are worth the risk. So I bond with people over food. The vocabulary of taste, technique and ingredients gives me a way to open up and ask questions. I’m not saying that all my food-based interactions abroad have been perfect. I am, after all, still me. But food has been my conduit for many meaningful exchanges and excellent stories.

Here are a few of the recipes I’ve collected over my travels so far.

Austrian Strudel

Of the cookbooks I bought on that fateful spring break trip to Central Europe, the one I got in Austria is my favorite. It was pocket-sized, with a blue fabric cover that was dotted with pink and orange flowers. The brief, vague sets of instructions inside reminded me of the language in my church cookbooks. The book seemed to say: “If you don’t already know how to make spaetzle, you have no business trying to follow this recipe for spaetzle.” I thought, challenge accepted.

When I got back to my flat in Cork, I decided to keep the good spring break times rolling by making a strudel from my little blue book. The traditional process begins with mixing up a dough of flour and oil and then gently stretching it by hand until it’s so thin you can read a newspaper through it. Then, you brush it with butter, fill it with fruit and/or a sweetened cheese mixture, roll it into a log and bake it. It’s sort of like a pie in roll form, but with a lot more painstaking work and much less butter. If you don’t think that sounds like a fun time on a Saturday night, I don’t know what to tell you – we’re very different people.

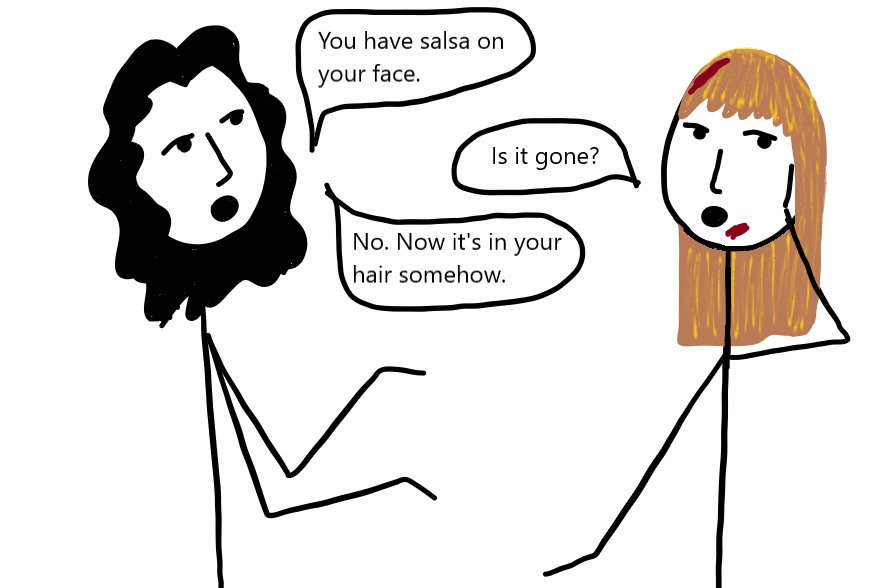

Somehow, I convinced my spring break traveling companions to come and watch me wrestle with the dough. Then, they helped me try to wrap it around a runny, sweet cottage cheese filling. Despite the mess we made on the counter, the strudel looked OK when I put it in the oven. However, when I checked on it 20 minutes later, I saw that something had gone very wrong. The roll had deflated, and the cheese filling was leaking onto the pan, creating a pale, amorphous mass of dough and dairy. You know how, in The Fly, Jeff Goldblum’s human body gets tragically, horrifically fused with the body of a fly? It was like my oven did that same thing to a cheesecake and a tray of baklava. And then that dessert got dropped from a second story window.

As soon as I saw it I burst into hysterical laughter.

“Caitlin,” my friends asked, “what is it? Did something happen to the strudel?”

“Oh no,” I said, wiping tears from the corners of my eyes, “it’s not a strudel anymore. It’s a monstrosity!”

I tried to capture the magic of Austrian strudel a couple more times after that spectacular failure – once or twice in college, and once for my Lutheran Volunteer Corps housemates. One of my housemates was German, and I asked him if he had eaten strudel growing up.

“What?” he asked. “I never heard of that.”

“Strooo-del.” I said, “It’s a German word…isn’t it?” For a minute I panicked, wondering if strudel is just a joke that Austrian locals play on tourists, like the Hard Rock Cafe or Malört. “It’s a pastry with dough and apples…”

“Ah! STRU-dl,” my housemate said in the proper German accent. “Yes, I know what that is.”

If I remember correctly, that apfelstrudel finally came out the way I wanted it to. It had crisp, layered dough and flavorful apple filling that didn’t leak everywhere. My German housemate – and all my other housemates – approved. Briefly I thought, “Maybe strudel is my thing now!”

Reader, I did not make another strudel for almost a decade.

Italian Espresso

At the tail end of my semester abroad, I spent five days in Italy. My friend Giada had family there she had never met before, and she invited me to come along while she visited them. Her relatives spoke no English, and Giada didn’t think she spoke any Italian. However, when we got there, we found out that wasn’t quite true. Apparently, Giada’s mother had spoken Italian to her until she was about three. That left enough language buried in the recesses of Giada’s subconscious that she could miraculously understand about 60 percent of what her aunts, uncles and cousins where saying. I had no such magical Italian powers.

During one meal with Giada’s family, her aunt gestured at her and said something to another relative. Giada translated for me: “She says I know a little Italian,”

The aunt then gestured at me. “…Zero Italiano,” she said.

I did not need Giada’s translation that time.

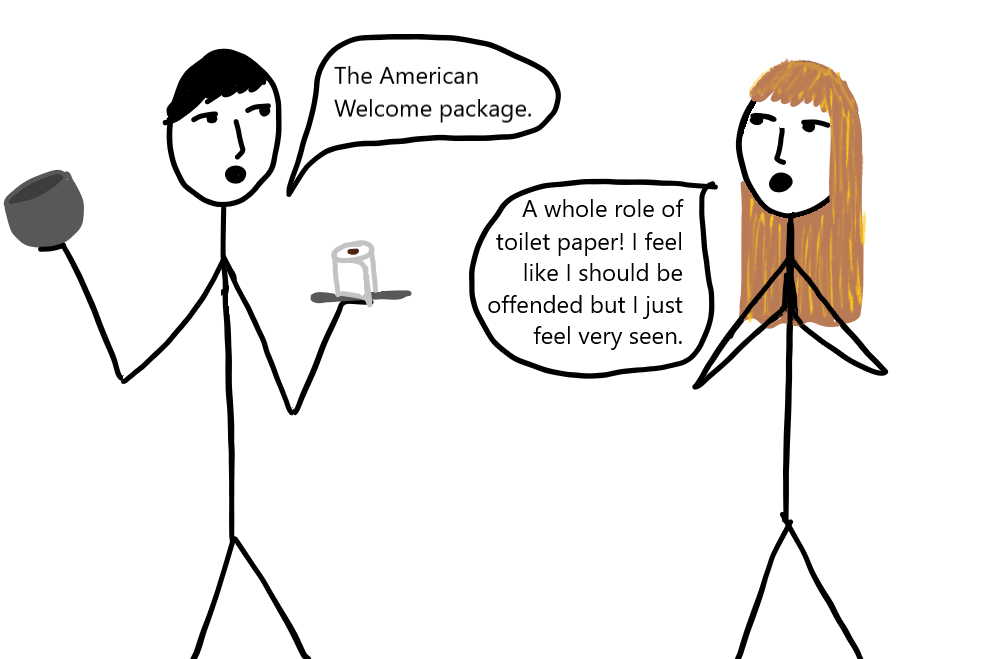

Regardless, I found Giada’s family warm and welcoming. We stayed with her great uncle in his small Florence apartment. Every morning, he set out a vast array of pastries for breakfast. He also brewed thick, strong coffee in a silver pot on the stove, then poured it into tiny ceramic cups for Giada and me. The first time he did this, Giada and exchanged panicked glances. We weren’t coffee drinkers at the time. Even the weak drip stuff was too bitter for both of us. But it seemed rude to refuse. Also, even without the language barrier, I suspected that “I don’t like coffee” would have been a difficult concept for an Italian to understand.

But then, Giada’s uncle filled two bowls with warm milk and gestured towards our espresso cups. Giada explained, “he says we can pour our coffee in here if we want.” Immediately, we dumped all of our espresso into our bowls.

“This isn’t bad,” Giada said after she took her first sip.

“Yeah,” I replied, scooping three more spoonfuls of sugar into my soup-sized latte, “Maybe I like coffee now!”

It would take a few more years, but eventually the hard reality of adulthood would winnow me into a daily coffee drinker. And shortly after I moved into my Chicagoland apartment, I bought myself a tiny silver moka pot, just like the one Giada’s uncle used. I still think of him, and of Florence, almost every time I use it.

English bread and honey

Several years ago, I visited London for a couple days following a trip to Wales. While browsing Airbnb for a place to stay, I came across a room in a shared residence that was so alluring, I was worried it might be a trap set specifically for me. The host, Tom, wrote that he was a journalist, cookbook author and urban gardener. For breakfast, guests could have freshly baked bread, honey from bees he personally owned, and eggs from the chickens in the coop in his back yard. Anne, who was travelling with me, agreed that it seemed almost suspiciously perfect – but worth the risk.

After we booked the room, Anne wound up having to cut her trip slightly short, leaving me on my own in London for a day. I wasn’t too worried – especially once we arrived and found Tom’s family home as lovely as advertised. On the morning of my last day in London, I said goodbye to Anne and set out for some solo sightseeing. Mid morning, I got a text from Tom. He and his wife were having a few friends over for dinner. Would I like to join them? First I thought, “that sounds like an awfully long time to act normal in front of strangers.” Then of course, I RSVP’d yes.

That evening, when I returned to Tom’s house, the rest of his guests had already arrived. I was welcomed to his dinning room table and introduced to half a dozen of the coolest people I’d ever met. I found out Tom’s wife wrote children’s books, and a few other guests worked in the publishing industry. Two women there lit up when I said I was from Chicago. They were academics, and had lived in Hyde Park for eight years. I was thrilled to have something in common with them. For a moment, I felt a little less out-of-place. Then, one of the academic women said something about Indian politics and everyone chuckled in a way that made me sure I had missed something.

One of the other guests leaned towards me. “Oh,” he said, “did we mention that she’s Ghandi’s granddaughter?” I raised my eyebrows.

“Um, no.” I said, “I don’t think that came up.”

I looked back at the academic woman and she gave a little, “guilty” shrug.

The out-of-place feeling was back.

But my discomfort faded as the cheese souffle bowls were cleared and the ice cream was brought to the table. I was both completely included in the meal and completely outside of my normal life. I became content to enjoy the surreal moment for as long as it lasted.

As the dinner wound down Tom said, “thanks for joining us Caitlin. We love the randomness of having you here. Um, not that you’re random.”

“Oh, no offense taken.” I said, “I’m a proud accident.”

I left the next day with a signed copy of Tom’s cookbook, a tiny jar of honey from his bees and and an Airbnb review from Tom: written proof that, for at least one evening, I was a great dinner guest.

Indian Thali

In 2016, I traveled to India with my mom, my aunt and my friend Christa to visit my cousin and her husband where they were living in Mumbai. I ate dishes on that trip with flavors so vivid that I can almost still taste them, four years later: little crunchy balls filled with a lentil broth that we ate in one bite, standing next to the vendor on the street; sweet, bitter chai cooked in a metal bowl over an open flame; a full rainbow of sauces, dhals and currys dolloped onto our plates by a choreographed team of servers at a thali restaurant.

There were also a couple of memorably puzzling meals – usually when our hosts tried to cater to our American tastes. The heritage hotel we stayed at in Agra had a huge, international breakfast buffet. It included everything from masala omlettes to meats and cheeses to pancakes and donuts. We assumed that last section – the one with all the carbs – was geared towards the hotel’s American guests. I took a donut and split it with Christa.

“Hmm,” she said after she took a bite, “this is OK…”

“It tastes like…” I took a minute to chew and search for the right comparison “…a hamburger bun.”

“Yes!” Christa said, “a sugar-covered hamburger bun!”

As Christa said, it was like the chef had seen a picture of a doughnut once and was like, “I think I got it.”

I didn’t mind. It was like being a part of a fun game of culinary telephone. And it gave me a tiny taste of the confusion Indian people must feel when Brits and Americans come up with recipes like curried mac and cheese and chai latte marshmallows.

I also took my first and only formal cooking class on that trip. It was with Anjali Pathak, who my cousin called, “the Indian Martha Stewart.” Anjali is the granddaughter of the founder of Patak’s – a company that manufactures sauces and chutneys that are available in grocery stores around the world, including Walmart. She grew up in the U.K., but moved to Mumbai as an adult to build her own brand.

Anjali met me and my travel companions in her kitchen classroom for a private lesson. The space was quiet, spacious and covered in black marble. She was a petite, glamorous woman wearing a pink chef’s coat. She greeted us, touched up her berry-colored lip balm, then patiently walked us through how to make our own healthy thali. We learned techniques for peeling ginger, testing chili spiciness and shaping chapatis. When we were finished, we poured our sauces into a row of little silver bowls and lined them up next to our aloo tikki and chapatis on ‘gram-worthy serving platters.

I bought one of Anjali’s cookbooks, of course, which she signed for me. She also sent us out with copies of the recipes we made that night. Still, even though I had just prepared the food with my own two hands, I knew it wouldn’t taste the same when I made it again in the U.S. That’s how it always is with the fleeting magic of the food I eat abroad. I can only take a list of ingredients home with me. The rest of the experience – the place where I sat down to try it, the group of people I ate it with, and even the person I was before I took the first bite – I have to leave behind.

Look, I don’t want to over-sell the unifying the power off food. I’m not going to declare that, if all of society could just sit down and share a meal, we’d work out our differences. I am being sincere though, when I tell you that food has given me a way into real relationships. There have been times when I felt painfully distant from people with different backgrounds and racial identities. When I worked with low-income residents in Baltimore, I had no idea how to ask about the things they were struggling with the most. However, I did know how to ask them their favorite way to cook eggplant. I knew how to hold hands with them at the table and say grace. Food did not “solve” those relationships, but it helped me take a step forward.

I know it may be a while, but I’m ready for more awkward conversations over shared meals. Until then, I’ve got my international cookbook collection to keep me entertained. I’ll keep using it to pay tribute to the wide world I miss so much.

And now, I have to admit that, yes, I did make strudel again a couple of weeks ago. Since I won’t be getting on a plane anytime soon, I must have been feeling nostalgic for my first international voyage as an adult. I wanted to relive the memory of making it in my Irish kitchen. And it worked – the process was just as frustrating and tedious as I recalled. Go ahead and click through to the strudel recipe on the next page if you’re looking for a challenge. If not, maybe just buy yourself a Danish and call it a day!

I love these articles. I”m hearing things I haven’t heard before,,

LikeLike

Someone is telling me I’m repeating myself. I don’t think I am but I will humour her and just say ⁵GOOD job. By to

LikeLike

Someone is telling me I’m repeating myself. I don’t think I am but I will humour her and just say ⁵GOOD job.

LikeLike