Sociological lessons from a church cookbook

Jump to recipe for chicken potato casserole

Of all my cookbooks, only one is falling apart from overuse: My childhood church’s cookbook. The comb binding is bent and letting the pages escape. The back cover has been gone for years. The page with my family’s go-to chocolate chip cookie recipe – marked with a yellow Post-it sometime in the 90’s – is almost translucent with grease stains. I borrowed it from my mom shortly after I moved to Chicago and promised I’d return it to her soon…about seven years ago.

I haven’t cooked from it much as an adult, but I like to have it in my collection. It is the purest artifact I have from the place where I grew up. Sometimes I pull it out just to prove to myself that no, I have not been exaggerating the importance of mayonnaise in my native culture. (In the cookbook it is used as a spread, binding agent or source of fat in salads, main courses, desserts and every kind of appetizer: dips, bites AND balls).

Food scholars and historians have studied community cookbooks because they’re so rich with rare cultural information. They describe dishes that have actually been fed to families and brought to potlucks and handed to sick neighbors. So, they provide windows into normal people’s daily lives. And they capture voices – especially women’s voices – that are missing in many other places.

Some cookbook authors try to harness the storytelling power of recipes on purpose. In 1886, a group of activists in Massachusetts wanted a lady-appropriate way to spread their feminist message. So they produced The Woman Suffrage Cookbook. It included recipes for things like “Rebel Soup” and “Mother’s Election Cake.” Most community cookbooks are less pointed, though. Their only agenda is to raise money for building repairs and quilting supplies. So, the stories they tell are random, candid and often accidental. Which is probably why I find them so charming.

My Lutheran church cookbook is just one of many mayo-filled tomes, produced by amateur cooks across the country. It probably isn’t going to make it into any lasting archives. But if it does – if some grad student stumbles across it several decades from now while looking into rumors about a bygone era of free, unprotected potlucking – a close read will reveal some important things about the community it came from:

1) An efficiency of language

Wording throughout the cookbook is spare. Most of the recipe instructions are just two or three sentences long. Some of them include a brief epilogue about who the recipe came from or where to serve it (i.e. at a brunch or on on the way to a hockey tournament). Some of the entries seem more like lyric poems about ground meat than instructions for cooking. A recipe for “Quick” calls for seven total ingredients. Three of them are cured meats and two of them are biscuits. I can’t tell, from reading the instructions, if “Quick” is a sandwich or a casserole, but I believe the recipe author when she says it is a “good snack.”

To get a sense of the scope of Minnesotan vocabulary though, you don’t have to look further than the recipe titles. They can be divided roughly into three categories: efficient, cultural and mystery. The majority of the recipes fall into the efficient category. They simply let you know what you are about to eat. Examples include: “Turkey Cheddar Rice Bake,” and “Apricot Coconut Balls.” The cultural titles are mostly traditional names for dishes that have been handed down from Scandinavian family members, like lefse or kringler. A few make transparent attempts to tack an air of worldliness onto plain, Midwestern foods. (I’m looking at you, meatloaf au fromage.)

The mystery titles are, of course, the best ones. They give almost nothing away about the dishes they describe. My favorites include: “Notable Dip,””Luncheon Meal (Delicious),” “Oven Stew,” “Mystery Fudge,” and “Piccalili.” The last line of the Piccalili recipe cheerfully announces, “A favorite at bridge parties. (I have no idea what the name means!)” These titles demonstrate that, just because church ladies don’t fill their recipes with puns or flowery descriptors, it doesn’t mean they don’t know how to build drama.

2) An artistic interpretation of salads

A few years back, the New York Times published a compilation of 50 Thanksgiving dishes – one from each state. Minnesota’s dish was a thing called “grape salad,” which consisted of whole grapes, sour cream and brown sugar. The dish was to be warmed to “luke” in the oven, then chilled again. It caused a bit of an uproar in Minnesotan circles. I have never heard of grape salad, and neither have any of the other Minnesotans I know. So, the article seemed to reveal that no one from the New York Times had bothered to fact check this with anyone from our state. If they had, they would have found out that the actual “salads” we put together are much more creative and depraved than a cold bowl of grapes and sour cream.

In Minnesota, “salad” can refer to anything that has chunks, and is scoopable. There is usually at least one fruit or vegetable, but that’s not a requirement. This includes “regular” salads with lettuce and croutons and other boring ingredients for normals, but it also includes salads made of jello, candy bars, marshmallows and whipped cream. The “Salad” chapter in my church cookbook kicks off with not one, but two recipes for “cookie salad.” Later, there is a whole subsection of “congealed salads” that’s full of fruited jell-O molds. All are to be served alongside antipasti and ceasar salads. Again, who says church ladies don’t know how to have fun?

3) The practicality of hotdish

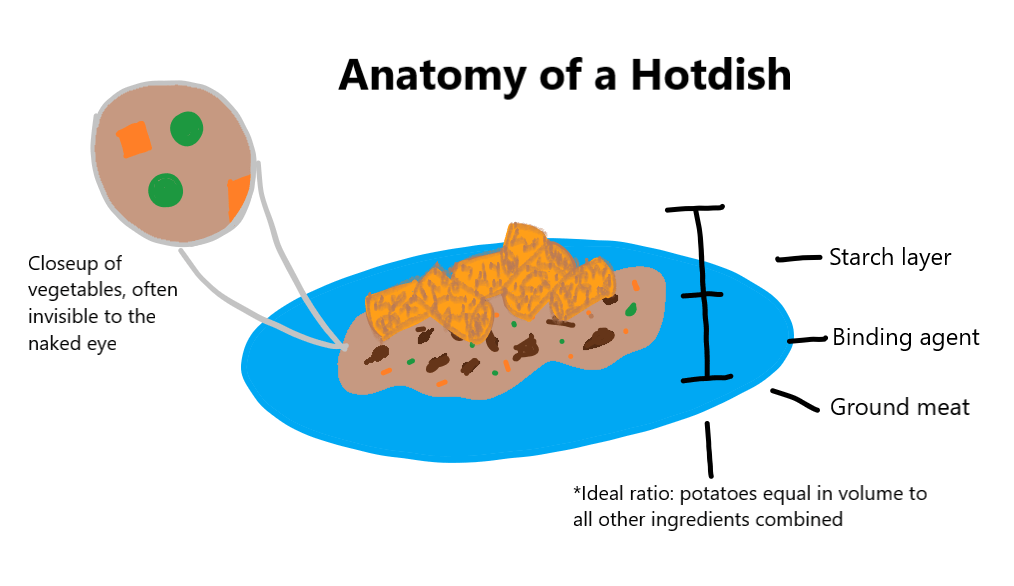

The simplest way to explain “hotdish” is to say that it’s a regional word for casserole. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. Casseroles can be full of fancy ingredients like white wine and fresh herbs and cheese you have to get a Whole Foods associate to slice for you. You can slave all day over a casserole. A hotdish comes together in 30 minutes or less. It is an unpretentious mix of a protein, a starch, some optional vegetables and a binding agent – cream of mushroom soup is most traditional. Over the years, I’ve looked for a colorful origin story for hotdish. I couldn’t find one. It seems to invented itself out of leftovers and necessity.

Hotdish was often at the center of my family’s table when I was growing up, and it is at the philosophical core of my church cookbook. The “Main Dishes” chapter has a few notable hotdishes. The “Chicken or Turkey or Tuna Hot Dish” calls for two cans of “cream of” soup, Miriacle Whip and Velveeta. The page is dogeared. There are also some chicken bakes and noodle pies that adhere to the basic hotdish formula of meat + starch + goo = dinner. All of these dishes embody a Minnesotan cooking philosophy that I’ve come to appreciate more, the longer I’m away. It’s about finding the nexus between of love and practicality. It doesn’t matter if you don’t have expert knife skills, or access to fresh vegetables, or more than an hour between work and play practice. What matters is finding a way to use what you do have to bring people together around the table. And as a bonus, if you use Velveeta, they’ll ask for seconds.

4) The love language of dessert

Cakes, cookies and desserts take up over a third of my church cookbook – and that’s not including the doughnuts, caramel rolls and coffee cakes in the “Bread and Pastry” chapter. At first, it’s hard to find a unifying theme between all these sweets. They run the gamut from the standard banana bread to the mysteriously titled “Pig Cake,” which calls for oleo and the juice from a can of mandarin oranges. But they all have a few things in common: They produce large batches, and they are meant to make people happy. I can tell that much from the formula for sugar cookie dough packed with gumdrops; and the instructions for making jack o’ lantern faces out of raisins on top of the Great Pumpkin Cookies; and especially the ingredients for Better Than Sex Cake – which is a chocolate cake from a boxed mix, fully saturated by sweetened condensed milk and caramel ice cream topping. These recipe authors want to share joy.

Of course, right now, I can’t share anything the way I want to – especially baked goods. But I can still speak the love language of food. Community cookbooks have declined in popularity since the internet has given us faster, flashier ways to share recipes. But now, in the midst of the pandemic, community cookbooks are making a comeback. Work colleagues, communities of faith and extended families are exchanging recipes over email and on shared Google-docs. They aren’t doing it to become better cooks – they’re doing it so that they can feel closer to each other. So, those digital recipe collections are providing the same thing church cookbooks have provided for a hundred years: A way into each others’ kitchens.

The recipe on the next page is a sort of tribute to church cookbook main dishes. But, by my own rubric, it does not actually qualify as hotdish. There is no Velveeta or cream of mushroom soup and it took longer than 30 minutes to make. But it is scoopable! And it is ready to go directly from my kitchen to yours.

My family makes a salad recipe that would fit in the church cookbook. The “fruit” ingredient is cherry pie filling, and other main ingredients include cream cheese and whipped cream. We primarily eat it for Thanksgiving, and serve it with the main meal (not dessert). CP has always been very skeptical. I don’t know why. It is delicious and has fruit in it, so clearly a salad.

LikeLike

I don’t think I knew what a real salad was until McDonald’s came out with those shakeable ones in middle school. 😁

LikeLike